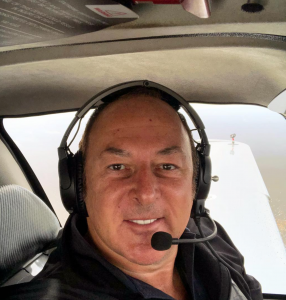

Skylark – WA oncologist Dr Andrew Dean shares his passion for aviation

As a young boy, Andrew Dean was fascinated with aeroplanes. But the son of Liverpool publicans quickly realised that flying lessons were a lofty pursuit his family probably could not afford. It was many years later, after training first as a palliative care and internal medicine physician that the medical oncologist decided his sky-high ambition was finally within reach. At 36, he began thrice weekly flying lessons. Four months later, he was a qualified pilot. Now, in his pride and joy, a Cirrus with the number plates India Charlie Echo (or “the ICE baby”) he bypasses bustling freeways and heads as high as 17 and a half thousand feet above the clouds to visit patients every week in Geraldton, a regional WA town that’s a five hour drive from Perth but takes this skylark just over an hour. Andrew says the journey is great thinking time, constantly exhilarating and always breathtaking. That’s not to say he’s never had a worrying moment. In his glass-cockpitted, blue and silver pride and joy, he’s traversed Hamilton Island, Broome and Ayers Rock. Sometimes, he’ll even offer a lift to country patients who need to get to the city in a hurry. For the self-described “aviation geek”, this passion for all things airborne goes well beyond a hobby. Still, he muses, there are some definite parallels between treating cancer and flying planes. And, at the end of the day, the cancer patients he treats always bring him back to earth.

What sparked your aviation obsession?

I just loved flying, since I was a little boy. I didn’t do anything about it because I probably couldn’t afford it. Never once did I dream I would be able to do it. I looked at planes enviously and thought how amazing it would be to be flying above the clouds. Then, in 1998 when I was 36, I just decided it was about time I learnt to fly. I took myself down to the aero club, did about three lessons a week and four months later got my pilot’s license. I was just hooked from the first moment.

Describe the experience for the uninitiated.

You race down the runway, you see everything flashing by your periphery. As you pull back it is just this soaring sensation … you see everything below you and it’s like you just leave all the worries of the world behind you. Then, when you soar above the clouds, you see this carpet beneath you. It might be grey and raining below, but when you soar up through this hole, it can be sunny and below you is just this carpet of cotton wool cloud. Although it is very technical, it’s so absorbing but so relaxing and exhilarating all at the same time. Bizarrely, when I land I feel as if I have had a massage. I get in the car and I usually start yawning.

Scariest moment?

I have had an electrical failure at night, when there is no moon, no stars and no light.

I was flying over (WA’s) Cervantes, doing a leisurely orbit over the Pinnacles. Suddenly I realised that the strobeascopes on the wings, instead of blinking every couple of seconds, were blinking about every 10 seconds, and I thought, ‘uh oh’. I literally switched absolutely everything off in the aircraft and hoped there would be some residual battery. As darkness fell, there was no moon and no stars. I had to navigate with a compass and a little red torch that you carry at night time. As we got close to the city, I put the radio on and put out a call.

They said how many POB – short for how many people on board. It really means how many body bags are required.

They told me to contact them again over the coastline, and they said we will put the lights on at Jendicott (airport). It was difficult to land because you can’t put the flaps down, you have to come in quickly and you are landing without lights and putting gears down by hand.

Obviously it all worked, thankfully. Through all of this my passenger was pretty calm. He was the head of a bomb disposal squad in Hong Kong and used to sitting on top of unexploded bombs. He was more bemused that I did not realise sooner that the electrics had failed.

Do oncology and aviation have any parallels?

They are both fascinating, absorbing and you learn something new every day. You learn something new every time you fly. Like every patient is different, every flight is different. Both require 100% attention and both are very rewarding. You get used to thinking on your feet when problems crop up. As in oncology, you have a standard way of dealing with problems.

What do your patients think?

When you have somebody who is sick in Geraldton, it is nice to be able to say, ‘you really need to get down to Perth and do you want me to give you a lift down there tonight?’

You do get a good chance to talk with them and I think it’s inevitable that you form a bond. In oncology, you meet so many different people from so many walks of life. It is a privilege to know people in that way.